The Taylor Lorenz Paradox: ‘If I Can’t Work the Register, How Do You Expect Me to Make Any Money?’

A recent kerfuffle between legacy journalists and a Substack provocateur over promos has me thinking about exactly what the rules should be for indie reporters who don't have corporate backing.

At the advent of the Blog Age, media watchers and commentators, uh, commented on a key tension driving the movement to online publishing and concurrently undermining what was then a thriving corporate media industry. As legacy outlet ad revenue cratered through the 2000s and 2010s, no shortage of villains and scapegoats emerged.

Among that rogues’ gallery – Craigslist, Google, corporate mergers – some of the more prominent were bloggers, those pesky online authors and aggregators whose content was, largely, free. How can we, the serious, real journalists who draw paychecks from our corporate employers, compete for eyeballs against these hobbyist agents of chaos?

Agents of Chaos, Victorious

If you’re reading this, you probably don’t need me to tell you how that turned out. The digital warriors won. Today’s news hole – and the corps of reporters and editors who deliver it – has shrunk to a sliver of what it once was.

Gone are the days of city or regional newsgathering operations with hundreds of reporters blanketing beats like organized labor, import/export, retail, arts, state and municipal politics, and other coverage vectors that now mostly operate in obscurity. The remaining skeleton crews of paid journos mostly focus on the kind of salacious stories (crime, celebrity scandals, cultural commentary, national politics) that drive CPMs and make Chartbeat pop.

Reportage still exists for those other “niche” beats, but, ironically, the best of it has migrated to the spiritual descendants of those oft-critiqued bloggers of yesteryear.

Now, for good labor reporting or analysis of specific industries, you’ll have to search in places like Substack, YouTube, podcast players or micro publishers online whose only overhead is hosting their WordPress site and paying rent. (Worth noting that last week, news broke that the once-stalwart blog tool Typepad is slated to be decommissioned next month.)

The folks delivering this coverage are a mix of journalists who once worked these beats professionally but were laid off, well-sourced subject matter experts with independent income or wealth, and obsessive cranks who simply will not shut up.

While this new wave of rogue cowboys represents a significant portion of the modern reporting landscape, there are still journalists drawing paychecks at traditional outlets that continue to shrink through attrition. And sure enough, a residual tension still exists between them and the cowboys.

Taylor Lorenz & Her Many Haters

You guessed it, this is an X.com media drama post!

Taylor Lorenz is a tech and culture journalist/opinion-haver whose outspoken stances and myriad online antagonizations have made her a lightning rod for the worst people on the internet (mostly on Twitter/X.com).

Her resume reads like a J-school undergrad’s dream, with high-profile stops at The Daily Mail, The Daily Beast, The New York Times and most recently The Washington Post as well as lucrative book deals and a personal Substack called User Magazine which has more than 80,000 subscribers with annual subscriptions running $80-per-year. For our purposes, we’re concentrating on her current status as a successful, semi-indie Substacker.

Last week, Lorenz published a very popular piece on Wired.com about a clandestine Democratic Party project to manipulate liberal content creators behind the scenes.

Concurrently, Lorenz’s most recent purported scandal came at her not from the right, but from decidedly liberal-center members of the mainstream media who took issue with a very specific promotion.

Conflict of Interest Dog Says “Bark”

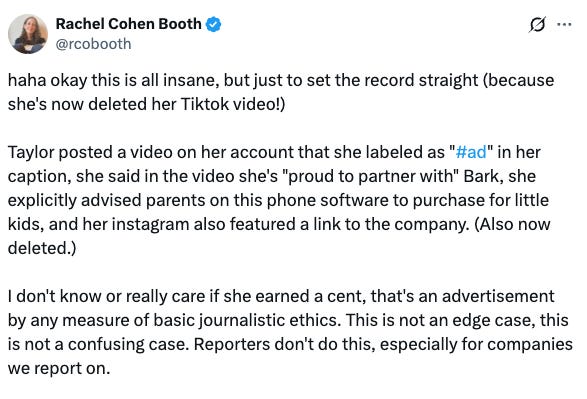

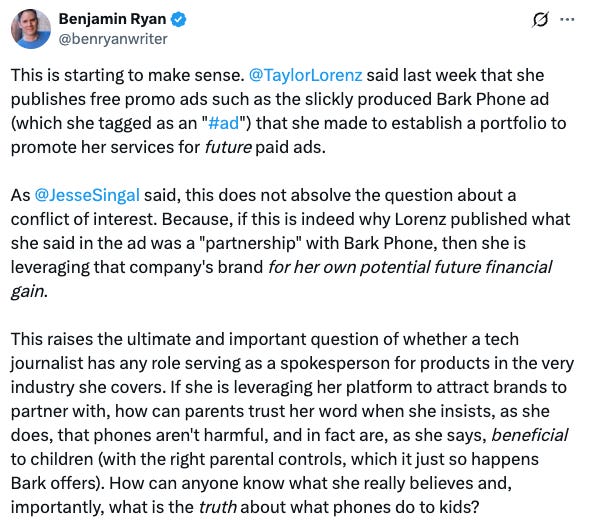

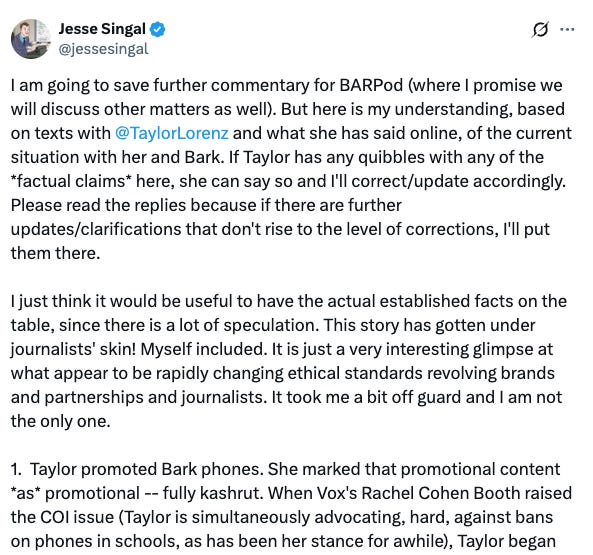

Lorenz in recent weeks shared content promoting Bark, a software company that claims to help kids as young as 6 interact safely with the perilous world of the internet. Users on X.com including online gadfly Jesse Singal, Vox reporter Rachel Cohen Booth and multi-outlet independent reporter Benjamin Ryan (perhaps best known for his New York Times bylines) took her to task, pointing out a conflict of interest as Lorenz has asserted that children should be allowed to bring phones to school.

They also criticized Lorenz broadly for forging a partnership with a company operating within her area of coverage (a huge no-no in the bygone era of journalistic conflict-of-interest ethics, which seems so quaint in 2025), then for not disclosing the true contours of the partnership (Lorenz tagged the promo as an #ad but later provided proof that she was not paid) and finally for User Magazine’s business plan – the Bark promo was just a test-run, according to Lorenz, a way to build an ad portfolio she could then market as inventory.

From there, the kerfuffle descended into Lorenz calling her critics old and implying they don’t know how to use the internet while threatening legal action, and in turn her critics – specifically Ryan and Singal – devoted a not insignificant amount of time into giving the scandal the Zapruder Film treatment across girthy threads.

Last I checked it had devolved into a real “he blocked-she blocked” situation.

***Tinfoil Hat Alert: I don’t want to get into this because it’s not the crux of this post, but I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Lorenz’s promotional content was thoroughly examined mere days before the Wired.com article dropped. But anywayyys… /tinfoil***

So, What Are the Rules?

In the past, Lorenz has been compensated (quite well, no doubt) by the biggest outlets in journalism. But most reporters have not led so charmed a life, and as the landscape of reporting has changed, many have turned to the Substack subsistence existence to maybe scrape out a living.

Consider: If I’m a reporter who was laid off by my shrinking news outlet, but I’m one of the only people still covering my beat, maybe I can eek out 1,000 subscribers paying, I dunno, $6 a month. That’s a nice wage! You might even be able to afford healthcare and rent in a mid-size American city!

But what if I need to earn more than that because my work is based in an expensive media market like New York, Los Angeles or the Bay Area? Or what if it involves travel, software, subscriptions, legal fees, or some other overhead? What if I have aspirations to grow my little Substack garden into something bigger? Or, what if I have the most banal, American reasoning of all – I’m just fucking greedy and want more money?

At most news outlets, this is something reporters don’t have to think about. The “Chinese Wall” is an old trope in legacy media, a prophylactic separating the pure-as-the-driven-snow journalists from the down-and-dirty ad dealmakers, lest there be any appearance of impropriety or implication that a writer was guided by commercial interests (as if all coverage isn’t, at its core).

During my years at the Miami Herald, that wall was a physical barrier – three flights of stairs separating the sales floor from the newsroom. Our hours and office space were situated in such a way we rarely interacted with our advertising/marketing counterparts. At Fusion TV, we occupied opposite ends of the Newsport campus. At outlets like Reuters and Televisa, I wasn’t even in the same city as our opaque bizdev departments.

Kicking Down the ‘Chinese Wall’

I think it’s wonderful Cohen Booth earns a living wage from a big company for her reporting. I think all good journalists deserve to be supported by a business operation that drives revenue so they can focus on impactful newsgathering. I also believe that the ideal configuration for the Fifth Estate was this old way, where reporters report and ad sellers sell ads and never the twain shall meet.

It’s unseemly for a reporter to have to cut business deals within their area of coverage. It sucks that those reporters can’t all just get gigs like Ryan and Cohen Booth (who, I should mention, authors a Substack that appears to be ancillary to her main reporting at Vox). Again, ideally, journalism would happen in a setting that looks like the Daily Planet.

But news media waved bye-bye to “ideal” decades ago in its race to the bottom. Today, indie/entreprenuerial reporters must sing for their supper. Yeah, it probably means their reporting won’t be as good as it used to be. But nothing is as good as it used to be, least of all journalism. And folks still gotta eat.

This is why I rankle at criticism like the kind aimed at Lorenz. Again, I’m sure she has no shortage of prospects to continue what has been a notable career. I’m more concerned about the precedents we set that constrain the prospects of people who are not backed by robust media outfits with entire floors worth of sales and marketing. That model is gone, folks, and I don’t think we’re allowed to be angry about what replaces it.

Working the Register for Fun but Mostly Profit

The dilemma brings to mind an old joke whose provenance I’ve long forgotten (I used to think it was from Chris Rock, but contemporary searches yield no results). Talking about his time working at a fast food restaurant, the comic observed, “if I can’t work the register, how do you expect me to make any money?”

Maybe it was Dave Chappelle.

In any case, unlike her allies and critics I mostly don’t care about Taylor Lorenz’s promotional deals or assignations. If she’s robbing the till, that’s between her and her shift manager. As a dad, I wouldn’t let my kid have a phone at age 6 (she still doesn’t have one at nearly 12) and I trust such decisions to better-researched sources (my wife and myself – in that order) than a childless tech reporter.

I do maintain some grace for the idiosyncratic and sometimes histrionic Lorenz because she has remained steadfastly correct on issues like masking, despite being a bit, uhhh, hyperbolic and mostly losing that debate in the public square. (Yes, a properly fitted N95 mask goes a long way to preventing the transmission of COVID-19. Yes, even crappy masks can help a little bit. No, I have no idea how this became a controversial statement.) Lorenz adhered to this position and others in the face of some of the most toxic vitriol you can imagine on Twitter/X.com. Good for her.

A Sneaky Double Standard

I don’t think her promotion of Bark will drive any more kids into the arms of harmful technology, as parents who buy it were probably already letting their kids rot away on far worse apps like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Roblox (all of whom have advertised on Vox, the New York Times, or both).

I also kind of don’t care if other parents let their kids burn out their dopamine receptors on phones because, cynically, that’s one less kid who mine will have to compete with in the coming resource wars.

I’m more interested in this question – what are the permissible methods for an independent Substack journalist to make money? Lorenz is in a privileged position, but many others are scraping by without freelance assignments like Ryan, whose work regularly appears in prestigious outlets like the New York Times, NBC News and The Atlantic. Cohen Booth draws her paycheck from Vox, so like salaried and freelance reporters she enjoys a layer of remove from the “business” side of publishing. She can be unconcerned with dirty dealmaking that would impugn her reporting.

When her Vox colleague Sean Rameswaram chooses to devote an episode of his podcast to the resurgent 27th season of South Park, does anyone make connections with Vox parent company Penske Media, whose profit model involves taking for-your-consideration advertising cash from studios like Paramount? Is that a conflict? Does anyone use that connection to call his journalistic integrity into question? No, partly because it’s an absurd assertion, partly because who has the time to be that media literate and cynical, but mostly because he enjoys the specific privilege of working at a brick-and-mortar established outlet that keeps him above the business fray beyond the occasional ad-read. He’s fortunate, because he works in a part of media with clear, defined rules.

So, can we agree on some rules?