Morning in an America Where Political Ad Spending Doesn’t Matter

As we bid a fond farewell to election season and its record ad blitz, how do we know political campaign ads really work? How do we know advertising works at all?

Happy Election Day!!!

(Sorry, I started this draft last Tuesday. Let me amend my lede.)

Happy post-Election Day Monday.

There’s no need to relitigate how we found ourselves heading into a second Donald Trump administration – literally everyone is already doing that. Rather, let’s take an opportunity to examine how this historic week in American history has unmasked just how superfluous and largely unnecessary linear advertising has become in our society – a sentiment some Democratic strategists might share today as they lick their expensive wounds.

IF THEY ONLY KNEW…

My wife and I are doing a re-watch of one of our favorite shows, Mad Men, for the first time since it ended in 2015. We’re about halfway through the show’s run and we’re finding it a soothing balm for those kid’s-out-of-the-shower-reading-herself-to-bed witching hours, a muted and visually sumptuous wind-down to lull us to sleep. (And it totally holds up, even better on a rewatch 10 years later.)

But when the show began back in 2007, there were no kids in the shower or in bed. A young 20-something couple, we had been dating about a year. My wife was the one who hipped me to AMC’s little-watched gem before the cultural intelligentsia fell in love with it. When I tell people how much I enjoy this show, I often get back some version of, “well that makes sense, it’s about your profession.”

They’re talking about advertising, an industry that was already ubiquitous and well understood by the average person before Mad Men.

This makes it unsatisfying and ultimately pointless when I try to explain that I work in “communications”, not “advertising”, per se, although my job often involves creating and arranging pieces of advertising, defining media strategy for larger overarching omnichannel campaigns aimed at multiple consumer and audience segments to affect specific behaviors and oh my God I think I just bored myself to sleep.

In lieu of pedantry, I prefer to respond, “oh yeah, there’s a lot of overlap,” and keep the conversation moving.

THE BLACK BOX OF GUTS

If I’m being honest, even 20 years into my career, advertising is a black box to me. Much of the sinew and viscera has been drained from that box over the intervening decades that saw Sterling, Cooper and friends enjoying 9 a.m. highballs to today, when tech has overtaken organic influence in the larger advertising globule.

Advertising was, in those days, a truly human endeavor with flesh-and-blood hands on every aspect from client management to creative to strategy. Guided – for good or ill – by broader data points, arbitrary client wishes, and old-fashioned intuition, advertising was in a gilded dark age.

A good primetime ad on a random Friday night in September could deliver actual, quantifiable bottom line results. This is no longer true.

Agencies charged enormous sums for their work and led lavish existences, and despite the few tools at their disposals they delivered outsized results. A good primetime ad on a random Friday night in September could deliver actual, quantifiable bottom line results and get people to talk. They barely knew what they were doing, these besotted leches of Madison Avenue, but what they did moved the needle because of its novelty. “Pictures on a screen telling me what to buy? Sold!”

This is no longer true.

ZEITGEISTS, ONLY ITTY-BITTY

Sure, there are the occasional linear ads that break through and capture the zeitgeist, but today’s “zeitgeist” is defined in increasingly smaller overall terms and those breakthroughs happen less and less frequently. My readers – communications people – might not realize this because we pay closer attention to these campaigns on a granular level. But for the general population disinterested in our world, advertising laps over the extremity of their awareness, like waves on your feet as you walk parallel to the shoreline, a feature of the geography you accept as extant.

Advertising obviously still exists, but in 2024 it has mostly become noise without signal, animated graffiti, something your awareness ambles past and barely registers. This goes beyond our shrinking attention spans and collective brain-rot. What I’m describing is more of an evolutionary response.

If you were born in 1980, you’ve been inundated with ad content emanating from every available surface, space, or screen you’ve interacted with for 44 years. While Donald Draper had an entire population of virgin eyes and ears poised for capture at the onset of a new era of mass communication, our 2024 senses have been shot through to the point that advertising has become little more than a contest of absurdity – see which cute and/or weird CGI creature can make the funniest face when it steals a beer or potato chips from a baby, add a celebrity cameo and/or a well-known Top 40 track, then pay $10 million for it to air on Superbowl Sunday (the only day of the year people pay attention to commercials).

(Or dump that $10 million into digital chumbox ads that appear as 200x175 pixel tiles at the bottom of content people actually want, hoping visitors will waywardly click on an image of an AI Sofia Vergara giving a middle finger with an ambiguous caption like, “How she told them ‘Never again!’”. But let’s save our rancor for digital ads for a future post.)

I don’t watch Mad Men to think about the depressing and perverse economics of brand elevation in 2024. I watch it to be reminded of a mythical era when Madison Avenue soothsayers could weave arcane magic to shape influence and drive revenue. To someone like me who is “in the profession”, it’s akin to high fantasy fables about dragons and krakens. I’m fascinated by the depiction of eras bygone when 30 seconds of images and sounds could affect consumer decisions, drive measurable shareholder value, and move markets.

Which brings me to the election.

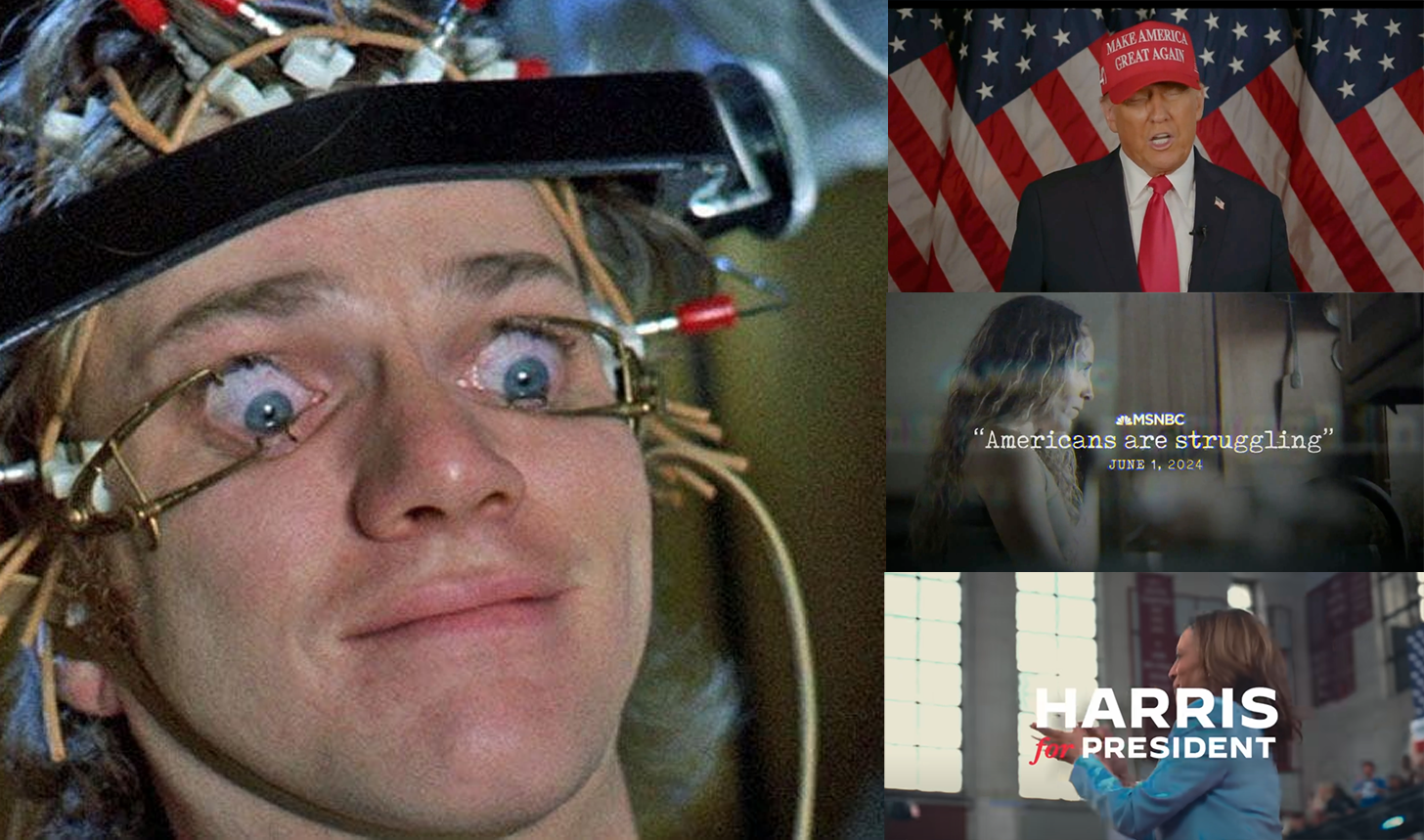

AD BLITZED

The New York Times podcast The Daily was out Monday with an episode devoted to a deep dive on the advertising campaigns of each major presidential campaign. AdImpact says that $10.2 billion have been spent on political expenditures across the 2023-24 election season, an ungodly amount considering most polls and pundits expect the final result to mostly mirror the past two quadrennial elections. Are minds being changed by ads? Do they raise awareness? Does the predictable cadence of a formulaic 30 second ad spot about a politician or issue, parodied almost to the point of ridiculousness, justify the spend?

I don’t know, but I’m not sure I can be convinced it does. Measurement in advertising – just like comms – is enigmatic and foundationally corrupted. It’s such a thorny topic, with indicators and metrics designed mostly by the same industry that insists on its own relevance. CPMs, impressions and Nielsen Ratings? I’d sooner trust my brand’s success to Tarot Cards. While social media once held the nascent promise of accurate engagement statistics, anyone who’s ever run a Facebook campaign can tell you how fudgy those metrics remain.

But since we’re talking about this election, a discrete moment in time, and since I waited until a few days after its completion, we can take this opportunity to judge ad results based on actual results.

Back in January, the national polling averages for the U.S. presidential election – then pitting Donald Trump against Joe Biden – had the latter with a <2% advantage (48%-46%). Most pollsters would consider this a statistical tie.

Fast-forward to August, and after tectonic shifts to the political landscape that included a viral debate failure, an assassination attempt, a new candidate, rising violence and tension across the Middle East, racial acrimony, ever louder evidence of a quiet recession, and spates of political violence, the polling averages had shifted all the way to... the exact same <2% Democratic advantage (48%-46%).

After another assassination attempt and some minor late fluctuations, and after we all learned the term “herding” together, the polling averages entered Election Day mostly the same as they had been. And today, if the current projections hold, the final difference will be about 51%-48%, a >2% spread (in the opposite direction) and still within the margin of error.

During this time, both parties had emptied out their coffers on television advertising, but Democrats significantly outspent Republicans. The Harris campaign spent $456.3 million on television ads to Trump’s $204.3 million. Each got a boost from outside aligned interest groups, including $364.1 million for Harris and $306.1 million for Trump.

So, after an election season that saw the political class drop more than the GDP of Grenada on television ads alone, can I ask you to do me a favor? Ok? I promise this isn’t a “gotcha”: Tell me your favorite TV ad for either candidate.

(Ok, maybe it’s a little “gotcha”.)

But really, which ad made you or someone you know reconsider an issue? Which ad gave you new information to think about? Forget about changing hearts and minds – did any ad get you fired up to go vote for whoever you were going to vote for?

Yeah, me neither.

Now, being inured to advertising is a standard-issue Xennial trait, so this isn’t much of a surprise to me. Maybe it’s not for you either. But when did political advertising become such a gormless, featureless, cash void? I picture political media consultants as the stokers in the engine rooms of the Titanic, shoveling loads of cash into furnaces as fast as it could possibly evaporate.

People might still “watch” TV ads, they might be on in between our programs. They might be colorful or dour or scary and their creators, brands, and the proprietors of the hardware that publishes them might be able to regurgitate raw analytics that suggest they are being broadcast to large numbers of people.

But it doesn’t matter. Some of us are still on the couch, but our attention has checked out.

THE PROBLEM GOES DEEPER

I see this as more than a politics problem. It’s the medium.

Every year, advertising persists institutionally within organizations. Budgets mostly go up year-over-year, in lockstep with other divisions and corporate America writ large. Brands and agencies (naturally) agree that if their spends declined, it would certainly harm their bottom line (despite some clear evidence to the contrary).

Maybe they’re right. I don’t think so, but I’m so cynical about advertising I’ve developed a combination of acute prosopagnosia and oppositional defiance disorder aimed specifically at anyone or anything trying to sell me something. So don’t take my word for it.

[I]f the effectiveness of political advertising is so ephemeral, how do we know it’s effective? How do we know any advertising is effective?

Instead, consider our Vice President. Kamala Harris spent $225 million on ads about the economy, but did anyone change their mind about blaming Democrats for inflation? She consistently polled 10-20% behind Trump on the economy. Defenders of her ad strategy will say without that spend, it would have been even worse, but how can we know that? How can you prove a negative?

Now, I’m not writing this in hopes of some mass abandonment of political advertising across television and other legacy media. (Although a girl can dream.)

Rather, I’m saying if the effectiveness of political advertising is so ephemeral, how do we know it’s effective? How do we know any advertising is effective?

As I said, I’m a comms guy not an ad guy, and not to mix up my metaphors but to a comms guy everything looks like a nail (if we were, like, hammers, whatever you get it). I think most branding problems can be solved with a better communications strategy, messaging, planning and activation.

I don’t want to wade into what each campaign did write or wrong in the messaging or presentation (they can pay me for that, my public sector rates are quite reasonable) but it seems that while the overall positioning of these candidates emanated from a lot of places – xenophobia, economic obliviousness, their followers, their surrogates, social media trends, gaffes, viral videos, near-miss bullets, vibes – I cannot recall a single instance where an advertisement on television moved the needle.

What if the Harris campaign had shaved off a mere $100 million from its ad buys (pocket change!) and funneled it into better strategy, better surrogates, better messaging and activating voters where they are (instead of in spaces where they increasingly aren’t).

If I was actually a political consultant, I’d tell my candidate to invest in your positioning, your strategy, and modern message amplification – not just blanketing every minute of The Price Is Right’s ad inventory with campaign commercials. These spots are worthless and overused to the point that they’ve become very expensive white noise. Use that money to connect with your constituents.

PS: Oh yeah, as long as we’re out here killing mediums for political advertising, can we finally get rid of the mass text messages? Talk about worthless and overused.